Rejection’s a bitch, isn’t it?

You spend hours crafting a series of killer story pitches and the editor writes back some variation of, ‘Nup.’

Or, more commonly, they don’t respond at all.

Even if your pitch and the subsequent story is accepted, the sub-editor may chop out all the little bits you loved the most.

And then, when your article is published, you have to deal with the commentariat trying to rip your face off.

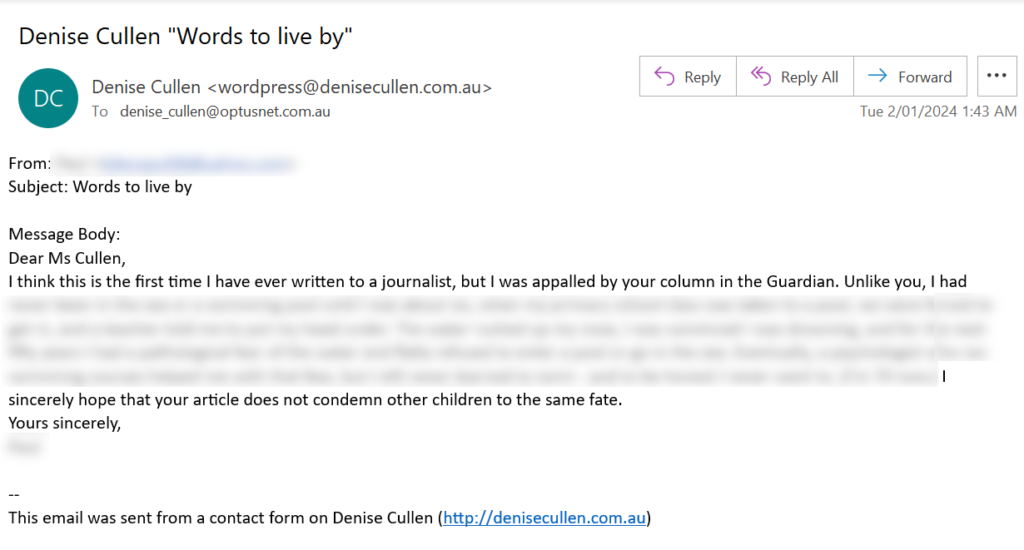

If they’re really upset with whatever you’ve written, they might even call or email you bright and early to give you a piece of their mind. (I’ve redacted much of what was included in the following email, as it contained lots of personal detail which I’m pretty sure the angry gentleman would not want shared.)

But back to pitching, which is a major pain point for almost every freelance writer I know.

When it comes to pitching editors, a straw poll suggests a success rate of anywhere from 1 per cent (beginner writers) to 50 per cent (top-tier freelance writers).

In other words, even top-tier freelance writers – those with long-standing relationships with editors and a proven track record of delivering high-quality work – are still striking out at least half the time.

(Read more about the number one mistake freelance writers make when pitching editors.)

The physical pain of rejection

Pitching is a time-consuming business that can, at its worst, feel a bit like begging.

But that’s not even the main reason the inevitable knock-backs hurt.

Psychological research suggests that, from a neurological point of view, there’s little difference between the pain of rejection and the pain from a broken arm or leg.

This makes sense from an evolutionary point of view.

Having the door slammed in your face feels like the contemporary equivalent of a Neolithic hunter-gatherer being cast out into the cold and forced to fend for themselves.

The prehistoric parts of our brain still respond to editorial brush-offs and other forms of rejection as though they’re a threat to our very survival.

Rejection, even gently worded, triggers a cascading effect through the rest of our brain.

Research has found that recalling a recent rejection was enough to cause participants to score significantly lower on IQ tests, tests of short-term memory, and tests of decision-making.

And even when others remind you “it’s not personal”, at some level, it still feels like it.

Which is why so many writers, sooner or later, quit.

I haven’t been able to find statistics for freelance non-fiction article writers.

But, Jane Friedman, who blogs on the book publishing industry, says more than 80 per cent of published authors quit within three books.

(That’s published writers, not beginners.)

About 10 per cent of published authors make it to six books. And only 5 per cent make it to twelve.

“A lot of people burn out and go to do something that doesn’t suck them so dry emotionally, over and over again,” she adds.

She makes the further point that those who succeed as writers aren’t necessarily the best writers.

They’re just the ones who are left.

They’re the last men and women standing because, despite all the odds, they refused to throw in the towel.

This uncanny longevity is often seen in those who rest – and try again – after rejection.

(Read more on The science of how rest makes you a better writer.)

So how else can I get better at coping with rejection?

In psychological circles, secure attachment is held up as the gold standard.

Securely attached individuals are those whose caregivers consistently met their needs in childhood and, as a result, they’re emotionally well regulated and comfortable being themselves in relationships.

The other three attachment styles – anxious, avoidant and disorganised – emerge as a result of varying degrees of dysfunction in childhood.

They’re usually seen as something to be ‘fixed’ or ‘treated’.

(Visit The Attachment Project for more information on attachment styles and to test your own.)

Rejection, of course, hurts no matter whether your childhood was a Hallmark movie or a dumpster fire.

But it’s often said that people with a secure attachment style are more resilient, more able to roll with the punches, more able to get back up when knocked down.

I suspect they’re exemplified in the following (somewhat nauseating) quote:

I love my rejection slips. They show me I try.

Sylvia Plath

Bully for her, but I see things differently.

My hypothesis is that people with an avoidant attachment style are far better equipped than others to cope with publishing’s rejection rollercoaster.

Upon being slapped in the face by the ‘no thanks’ email, or that eternally deafening silence, we’re less likely to turn Pollyanna (like Plath), or to crumple in tears (like some writers I know), than to feel an urgent need to prove them wrong.

The disappointment, the distress, and the frustration are no less real for the avoidantly attached.

But amid it all, we come out fighting, refusing to be discouraged, failing to give up and go home.

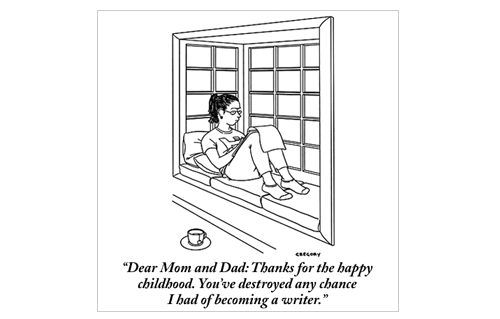

I love the following New Yorker cartoon by Alex Gregory. Don’t get it? My guess is you’re securely attached.

Dr Leslie Becker-Phelps, author of Bouncing Back from Rejection, writes that people with avoidant attachment tend to double-down in the face of rejection, driving themselves towards even higher levels of achievement.

She says it like it’s a bad thing.

But when the statistics are as grim as they are in publishing – and when the impact of cumulative rejection can be career-ending – it’s worth figuring out how to get past that first sting of rejection.

Using strategies from the avoidantly attached, it’s possible to turn that sting into fuel to power you forward.

The fact that even well-established writers still get rejection slips is one of the reasons why imposter syndrome is rife within our ranks. For more on imposter syndrome, read this.

Famous writers’ responses to rejection

I don’t (and couldn’t) know any of the following writers personally, but what they have to say about rejection seems consistent with an avoidant attachment style.

In 1985, Saul Bellow told The New York Times:

I discovered that rejections are not altogether a bad thing. They teach a writer to rely on his own judgement and to say in his heart of hearts, ‘To hell with you.’

Saul Bellow

In his blog in 2004, Neil Gaiman wrote:

It does help, to be a writer, to have the sort of crazed ego that doesn’t allow for failure. The best reaction to a rejection slip is a sort of wild-eyed madness, an evil grin, and sitting yourself in front of the keyboard muttering ‘Okay, you bastards. Try rejecting this!’ … Because the rejection slips will arrive. And, if the books are published, then you can pretty much guarantee that bad reviews will be as well. And you’ll need to learn how to shrug and keep going. Or you stop, and get a real job.

Neil Gaiman

And then – my personal favourite – there’s the masterful approach of Howard Frank Mosher, who peppered the side of his house with shotgun pellets every time he got a rejection slip or a bad review.

It should go without saying that you shouldn’t share you anger (or your shotgun) with the editor who turned you down.

But in a funny yet horrifying post titled When writers attack: Terrible ways to respond to rejection, editor Nathaniel Tower estimates that one in every ten writers will respond to a rejection, and not all of them are of the generous ‘Thanks for taking the time to read my work’ variety.

“One response used ‘fuck’ more times than a 2 Live Crew album,” he writes.

“It was so filled with hate that I wondered briefly if I needed to watch my back during the day and sleep with one eye open at night.”

(That writer wasn’t me. Just sayin’.)

Healthier ways to cope with rejection

In the wake of rejection, once your rage has subsided to a slow simmer, it’s worth exploring some other strategies to keep you sane, upright, and in the game.

Calculate the odds

Writing is all about taking risks – creatively, financially, and emotionally. The first is to treat pitching like the numbers game it is, in the same way that surgeons sometimes approach their work.

Some years back, when I was lying on an operating table, dressed in a surgical gown, with a stupid hairnet over my head, waiting to have my gall bladder removed, the surgeon came bouncing in and said, ‘Good news, I’ve already had one gallstone blocking a bile duct today.’

Seeing my confusion, he explained that, statistically speaking, he’d only see one patient per surgery day with this complication, and so the odds were that my surgery would be relatively simple. (And it was.)

Whether your pitching hit rate is 1 per cent or 50 per cent, each rejection literally takes you closer to a ‘yes’. If you’re a 10 per cent success rate person, send out 100 pitches, and you’re suddenly looking at more work than you can handle in a week.

Develop a thicker skin

To further cultivate the mindset of seeing each rejection as a stepping-stone, put them on display, rather than file them away.

Stephen King is legendary for his persistence in the face of rejection. He nailed his rejection slips to a wall until the weight of the papers pulled them down; he then replaced the nail with a spike.

It’s often stated that Carrie was rejected by more than 30 publishers, before it launched his career.

Play the philosopher

Jennifer Crusie is the master or reframing rejections or bad reviews.

Whenever one arrives, she just shrugs and says, ‘Not my reader.’

She is similarly pragmatic when a book doesn’t sell, saying, ‘I’m just building my backlist.’

Laugh in the face of rejection

Laughing at something takes away its power.

Matthew Reilly adopts a playful approach to criticism, reading his harshest reviews aloud at writer’s festivals, and thus transforming negativity into humour.

This diminishes the sting of criticism but also engages his audience in a unique way.

Learn as much as you can about pitching

Pitching is as much an art as a science.

Learning how to identify unique angles, tailor your pitches to specific publications and confidently communicate your ideas to editors is critical.

But your hit rate depends as much on relationships you build with commissioning editors as it does on your writing skills.

(My last pitch, to an editor I knew well, went something like, ‘Organoids in personalised medicine. Interested?’ This is not the way I’d approach someone new.)

Editors will sometimes suggest a tweak to your pitch if it shows promise.

But most of the time, you’re flying blind, with very little (if any) feedback forthcoming.

Which is why I’m developing a course on pitching for publication.

I can’t promise that it will soothe the pain of rejection completely, or even guarantee a 100 per cent success rate (see the statistics above for the reasons why).

But it will distil everything I’ve learned on successfully pitching hundreds of stories to newspapers, magazines, blogs and websites.

Sign up for the waitlist, and you’ll receive a FREE copy of three successful pitches to Australian and international publications, deconstructed.

In the meantime, let me know. What’s the hardest thing about pitching for you?