When I was in Patagonia last month, I should have been riding high.

I’d just spent one of the most magical weeks of my life swimming, surfing, hiking and horse-riding, alongside cruising the vineyards and restaurants of Chile’s lush Colchagua Valley.

And now I was in Puerto Natales, about to attend my first Adventure Travel World Summit, a massive event involving 700 delegates and 30 invited and fully hosted media from around the globe.

But even as I chatted to other excited guests at the media welcome drinks, I couldn’t shake the sense that I’d cheated my way into the room.

Imposter syndrome had joined the party too.

It manifested as a vicious little voice in my head which kept hissing variations of, ‘You don’t belong here, amid these hard-core adventurers, and high-profile editors, and revered photographers, and award-winning bloggers, and social media stars whose follower counts are measured in thousands or millions, rather than your piddling hundreds.’

(Full disclosure: It didn’t help knowing that I’d only been offered the spot after someone else dropped out.)

Over the next few days, as I got to know the other members of the press pack, I learned I wasn’t the only one who felt like a fraud.

I wasn’t the only one who believed that their presence was due to some sort of administrative error.

And I certainly wasn’t the only one who had the nagging sense that once they were ‘found out’, they’d be hastily packed off on the first flight home.

What is imposter syndrome?

The term ‘imposter phenomenon’ was first coined in 1978 by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes.

In 1978, they co-wrote a paper titled The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention.

The pair puzzled over the phenomenon in which certain women ‘do not experience an internal sense of success’, ‘maintain a strong belief that they are not intelligent’, and remain ‘convinced that they have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise’.

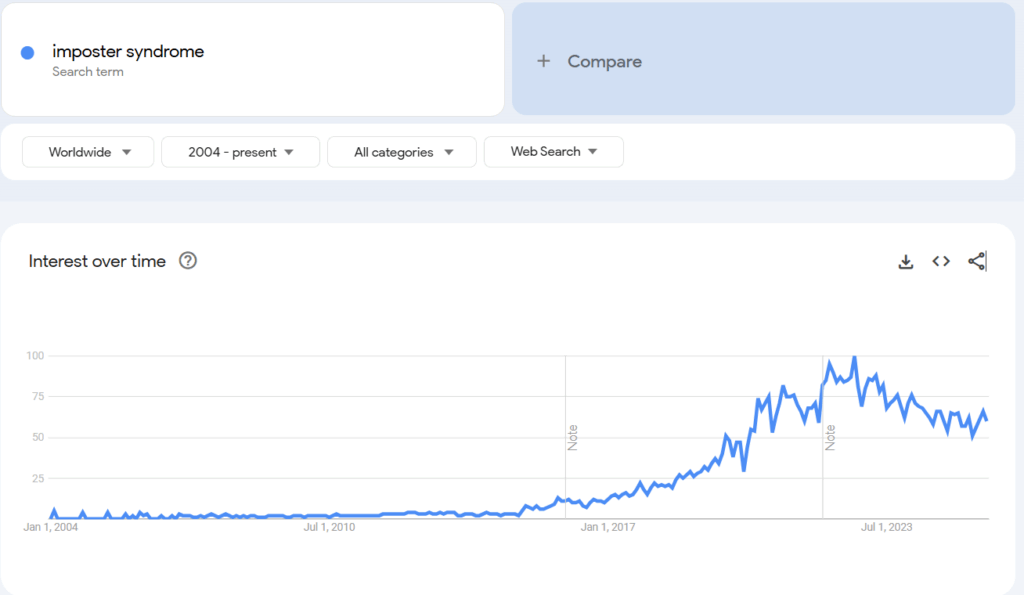

Since then, search traffic for imposter syndrome has exploded, due traditional and social media interest, and growing recognition that it is widespread experience affecting people of all genders and backgrounds.

As it turns out, imposter syndrome is also very common.

In May 2025, one meta-analytic review of 30 studies found that almost two-thirds (62%) of the 11,483 participants suffered ‘imposterism’.

The same article noted that imposter syndrome occurred when affected individuals ‘experienced anxiety, self-doubt, and feelings of alienation in situations where their abilities, performance, and competence are constantly evaluated’.

‘This sense of alienation, or ‘fraud’, is what gives rise to imposter syndrome,’ the article continued.

‘Imposter syndrome is characterized by a persistent inability to attribute one’s achievements to personal merit, instead attributing successes to luck or other external factors.’

And while it’s not part of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, imposter syndrome is associated with anxiety, depression, workaholism, perfectionism, burnout and more.

Why are writers prone to imposter syndrome?

As I kept digging deeper into this phenomenon, I discovered that it’s especially common among writers.

Literary legend Maya Angelou, whose works include I know why the caged bird sings, once said:

I have written eleven books, but each time I think, ‘Uh oh, they’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody and they’re going to find me out.’

And as John Steinbeck was writing his Pulitzer prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, he was keeping notes about his emotional state as he did so, writing:

My many weaknesses are beginning to show their heads … I’m not a writer. I’ve been fooling myself and other people.

There are many reasons writers are among the most likely to view themselves as imposters.

One is the subjective nature of creative work.

When there are no objective standards outlining what’s ‘good’ or what’s ‘bad’, it’s easy to doubt your abilities based on the subjective opinions of others.

A rejection, a request for a rewrite, or a snarky comment from an editor can easily send you into a tailspin.

Even when your work is published, it will be subjected to reviews and critiques.

Alternatively, the comments section will fill with remarks that range from witty to cutting to borderline deranged.

(Knowing that commentators typically can’t spell, punctuate or express themselves clearly, and objectively have too much time on their hands, doesn’t necessarily ease the sting.)

To read more about the challenges of freelancing, including ghosting and stalking, read this.

The precarious nature of freelance writing also helps sow the seeds of self-doubt.

Most writers must hustle REALLY hard and engage in a significant amount of unpaid work to chase a dwindling pool of paid assignments with remuneration and odds that are barely worth the bother.

Last week, for instance, I spent a few hours crafting three pitches to an editor following an industry-wide callout.

I know the editor personally, so she dropped me a lovely line afterwards, essentially saying, ‘Close but no cigar.’

She went on to say that she’d received roughly 200 hopeful submissions – but could only take on 2.

While I appreciated the note, this sort of numbers game easily leads you to question whether it’s even worth making the effort in the first place, or whether your time has any real value.

Then there’s the focus on external validation, such as awards, sales numbers, social media follower counts, or any number of other precarious measures.

Wrapped up in the average week, it naturally leads all but the most thick-skinned of writers to ask the question, ‘Am I really good enough?’

5 evidence-based ways to overcome imposter syndrome

Normalise and talk about your feelings

As I learned in Patagonia, if you’re feeling like an imposter, you’re probably not the only one.

It helps to remember that even famous, highly successful authors, with multiple books, awards and credits to their name, aren’t having an easy time of it either.

Discuss your feelings with members of your writing group, trusted colleagues, or personal mentors.

Build community through attending industry events and joining organisations such as the Australian Society of Travel Writers or the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance.

This can help you gain external perspective and challenge assumptions about how others perceive you professionally.

And the vulnerability and it takes to self-disclose can help to build new and nurturing connections that help get you through the tough times.

Ignore the evidence and just keep going

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is often recommended to address problematic thoughts, including those arising from imposter syndrome.

The general idea is to identify cognitive distortions like all-or-nothing thinking (‘If this pitch doesn’t land, I’m a complete failure’), catastrophising (‘If I don’t sell this story, I’ll never eat again’) and to tally up all the bits of ‘evidence’ that support your gloomy world view (or not).

But when it comes to freelance writing, there’s one big problem with CBT.

That is, there’s usually a mountain of evidence that one is, in fact, a failure and will never eat again.

Rejection rates are high. Financial rewards are low. The business, frankly, is rigged against us.

An approach called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is much more helpful here.

Unlike CBT, ACT does not obsess over whether a given thought is ‘true’ or not, but simply whether it is helpful.

ACT also shifts the focus towards values-driven action. That is, acting in accordance with your values and goals, regardless of the mudslinging happening in your head.

The measure of success thus becomes NOT whether a pitch lands or not, or whether a story sells or not, but whether you had the gumption to send it (or finish it) in the first place.

In other words, if writing is what you love to do, ignore the evidence you’re wasting your time and effort and just keep going, without the hope or expectation of any extrinsic reward. (Works for me.)

If you’re interested in exploring these ideas further with a trained therapist, visit the Australian Psychological Society’s Find a Psychologist website.

Practise self-compassion

ACT is also one of several therapeutic modalities which encourages self-compassion to counter the negative self-talk associated with imposter syndrome.

Self-compassion involves talking to yourself in the same way you’d address a close friend facing rejection or criticism.

As psychologist Kristin Neff points out, the first step is noticing, rather than ignoring, our struggles.

Turning towards our pain and exercising self-compassion cultivates a more supportive inner dialogue.

In doing so, we create and maintain the psychological safety needed to take creative risks and persist through inevitable challenges.

Some believe that self-compassion even improves the quality of your writing.

If you’re not constantly battling a nasty internal critic, you may be able to access deeper authenticity and emotional honesty, which resonates more strongly with readers.

For more information on self-compassion, visit Kristin Neff’s excellent website.

Challenge perfectionism

Perfectionism and imposter syndrome often go hand in hand.

The notion that every task must be done to the highest possible (i.e., flawless) standard is difficult to maintain when there are only 24 hours in the day.

Perfectionism means setting the bar so high that your goal is literally unattainable.

It manifests as difficulty getting going, because the idea is perfect in your head, but when you put it down on paper, the gaps start to show.

(Having trouble getting started? Read why task initiation matters more than you think.)

Perfectionism also shows up as endless hours of research, ten interviews when two would be sufficient, and multiple unfinished projects (because hitting ‘send’ literally means ‘this is the best I can do’.)

To overcome perfectionism, set ‘good enough’ standards, put time limits on tasks, and remember than done is always better than perfect. Freewriting might also help – more on that at this link.

Engage in writing sprints, word-count targets, or even using a pen and paper – anything to short-circuit your inner critic by reducing the stakes.

Separating the drafting and editing stages is another way to kick perfectionism to the kerb.

Give yourself permission to write an imperfect first draft. The only goal is to get ideas onto the page.

Treat them like raw material that you’ll refine later – because that’s all they are.

Read this for more ideas on tackling imposter syndrome and perfectionism.

Create a folder of ‘wins’

People who struggle with imposter syndrome often have a habit of shrugging off their wins.

But when you’re handed a rose, don’t be too quick to move onto the next task.

Pause for a moment. Smell the petals. Savour the colours. Bask in the glow.

Record specific compliments from editors.

(Yes, I know these might be thin on the ground. One editor I’ve worked with for more than six years is yet to say anything more expansive than, ‘Good job on X.’)

Keep a file of positive feedback from readers. (Yes, again, it’s rare.)

Save or print positive comments you receive from your peers. (In my experience, the people in the trenches alongside you are the most likely to cheer you on.)

When the chips are down and you’re ready to chuck it all in, pull out your folder, and look at all the lovely things people had to say.

By documenting every success, every skerrick of positive feedback, and any significant milestones, you create a concrete trail of evidence that, little by little, helps you internalise your success.

While you’re here ….

I invite you to subscribe to my newsletter. You’ll receive writing tips every fortnight, breaking news on courses currently under development, and a FREE copy of Pitching for Publication, which deconstructs three successful pitches to Australian and international editors.